|

| We Are Victims, Understand |

|

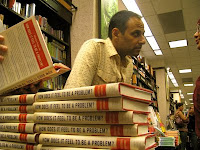

| Dr. Moustafa Bayoumi |

Bayoumi is the editor of How Does it Feel To Be a Problem: Being Young and Arab in America, a collection of biographical stories about young, Brooklyn-based Arab-Americans that the CMES website describes, among other things, as “a catalog of mistreatment and discrimination.”

Baymoui’s narrative of Arab victimhood extends beyond America’s borders—he is also the editor of, Midnight on the Mavi Marmara: the Attack on the Gaza Freedom Flotilla and How it Changed the Course of the Israeli-Palestine Conflict, as well as co-editor of The Edward Said Reader; victimization has long been a staple of his academic career.

CMES’s Sultan Room—so-named for its Saudi patron, the Sultan bin AbdulAziz Al-Saud Charity Foundation—was full. The audience of approximately 75 students and adults acted like fans; they laughed in all the right places, appeared to be in full agreement with Bayoumi throughout, and offered no challenging questions.

At the time, Egypt’s recent revolution was dominating the headlines and Bayoumi was on his way to speak on a UC Berkeley panel on the subject directly afterward. As a result, his lecture seemed rushed and, at times, the wording sounded remarkably similar to his October 24, 2010, Chronicle of Higher Education article, “My Arab Problem.”

Referencing the situation in Egypt, Bayoumi began his talk by quoting from The Autobiography of Malcolm X: “How is it possible to write about your life when it’s changing so quickly?” Later, he paraphrased Invisible Man author Ralph Ellison: “We are surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass.” He noted that his book’s title, How Does It Feel To Be a Problem, originated with a quote from W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk:

I stole the title from Du Bois; it resonated with me . . . what to do about the increasing dehumanization of the Arab American population.

Clearly, Bayoumi is heavily influenced by African-American literature—the chapters of his book are prefaced by quotes from famous black authors—but in equating African-Americans with Arab-Americans, he is conflating two very different historical experiences.

To support his position that Arabs, including Muslims, in America are “dehumanized,” Bayoumi cited polls conducted by the Economist and the Washington Post, which found—not coincidentally—a steady rise in negativity towards Islam beginning with the 9/11 atrocities and culminating in the Park51 (ground zero mosque) controversy. He omitted any possibility of a rational basis for these negative perceptions and later rejected what he called “the rhetoric of the opposition to the ground zero mosque.” Echoing the project’s organizers, he claimed that

This comparison is inapt in that the 92nd Street Y—in the secular tradition of Jewish community centers—does not include a synagogue, while Park51 is intended to include a mosque. Also, 92nd Street is not near a site where Jews massively attacked New York City.

Bayoumi next addressed the controversy that erupted in August 2010 after Brooklyn College assigned his book as its “common reader,” thereby making it required reading for all incoming students and setting up a “meet the author” discussion. Complaints poured in that the book was too lopsided and the debate eventually—as Bayoumi claimed the college feared—went “viral,” pulling him into “the center of a small culture war.”

Citing retired Brooklyn College philosophy professor Abigail L. Rosenthal, who, in a letter to college president Karen Gould, alleged that “the book smacked of indoctrination,” Bayoumi responded:

“Is my writing that powerful? No. They have not actually read my book, but only the Amazon page”.

He blamed the “tabloid media” and “conservative bloggers” such as Bruce Kesler—a Brooklyn College alumnus who broke the story by publicly cutting his bequest to the college over the Bayoumi decision—for the controversy. In fact, a variety of publications ran articles on the subject, including the Jewish Week, the New York Daily News, the New York Times, and the Huffington Post.

Summing up his thoughts on the matter, Bayoumi remarked that:

Opposition to my book seems symptomatic of our times . . . all things Muslim or Arab are called radical.

Bayoumi decried FBI counterterrorism efforts involving Brooklyn’s large Arab-American population, comparing it to investigating “the mafia; investigating family structures” and calling it “patronizing.”

The Texas revolution [sic] is another attempt to create controversy where really there is none. It’s contrived to give the idea that Islam is on the ideological march in the country. It bears little relation to reality. Those who point this out are accused of political correctness, of being duped, liberal, ideological warriors of political correctness.

He scoffed at “allegations of Arab investors taking over the American [textbook] publishing industry,” while his audience tittered. They were only too happy to mock such notions, despite significant evidence of these worrisome trends.

Bayoumi moved on to another favorite target of the Islamophobia-phobes, Middle East forum director Daniel Pipes. Selectively quoting from Pipes’s article on Brooklyn’s controversial Khalil Gibran International Academy, “A Madrasa Grows in Brooklyn,” Bayoumi stated:

Daniel Pipes wrote that ‘Arabic-language instruction is inevitably laden with Pan-Arabist and Islamist baggage.’

Predictably, he neglected to cite any of the examples that Pipes used to buttress this statement.

Bayoumi continued:

What is going on here? As soon as Muslims like myself are on the cusp of entering the mainstream fully, we are hit with a wave of opposition attempting to render us or our work invisible. . . . The trick is simply to attach the word ‘radical’ in front of a Muslim name, and, like a magician, make the actual person disappear in a cloud of suspicion.

Then he joked, “If you happen to be the president of the United States, ‘First Muslim’ will suffice,” to which the audience chuckled knowingly.

During the question and answer period, an audience member—perhaps referring, however inaccurately, to Pipes’s 2001 quote, “I worry very much, from the Jewish point of view, that the presence, and increased stature, and affluence, and enfranchisement of American Muslims, because they are so much led by an Islamist leadership, that this will present true dangers to American Jews”—asked:

Daniel Pipes says he fears Muslim expansion in America from the Jewish point of view. How much are these cultural wars intertwined with the fear among a segment of the pro-Israel, rightwing alliance of wanting to maintain a reflexive fear of Arabs and Muslims?

Bayoumi responded with a torrent of insults, buzz words, and generalizations:

There’s a nexus, and a major part is the Israel conflict. Pipes, David Horowitz—it all has to do with the production of Islamophobia. [It’s a] pro-Israel right wing attack; it’s a continuation of the rightwing, Christian attack on liberal education; a culture wars place where they’ve all arrived at that junction.

In response to an audience member’s question regarding the upcoming hearings on radical Islam in the U.S. convened by House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Peter King (R-NY), Bayoumi concluded that, “It’s part of the paranoia of today.”

Expanding on this theme, he then read aloud an oft-repeated quote from Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 essay, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, about the alleged paranoia and bigotry of the “modern right-wing,” which, he claimed, “you can hear in 2011.” Bayoumi has apparently bought into Hofstadter’s always dubious and now thoroughly discredited equation of conservatism with mental illness.

Moreover, chalking up the rational fears of the American public in a post-9/11 world to paranoia displays contempt and willful blindness. Such attitudes only allow apologists to delay indefinitely much-needed theological and cultural reforms within Muslim and Arab communities.

Bayoumi seems oblivious to the religious, economic, and cultural freedom that the U.S. offers. If America is such an intolerant, discriminatory country, why do countless Arabs and Muslims keep immigrating to its shores? According to statistics compiled by the Department of Homeland Security and the Census Bureau and cited by the New York Times, more people from Muslim countries became legal permanent U.S. residents in 2005 than in any year in the previous two decades. In addition, a 2007 Pew survey found that Muslim Americans, including many Arabs, are equally, if not better, educated and more affluent than the national average.

Instead of proclaiming a culture of victimhood, Bayoumi might acknowledge this encouraging reality. He could start by turning his book into a series and titling a forthcoming volume, How Does It Feel to be a Fabulous Success? Being Young and Arab in America.

No comments:

Post a Comment